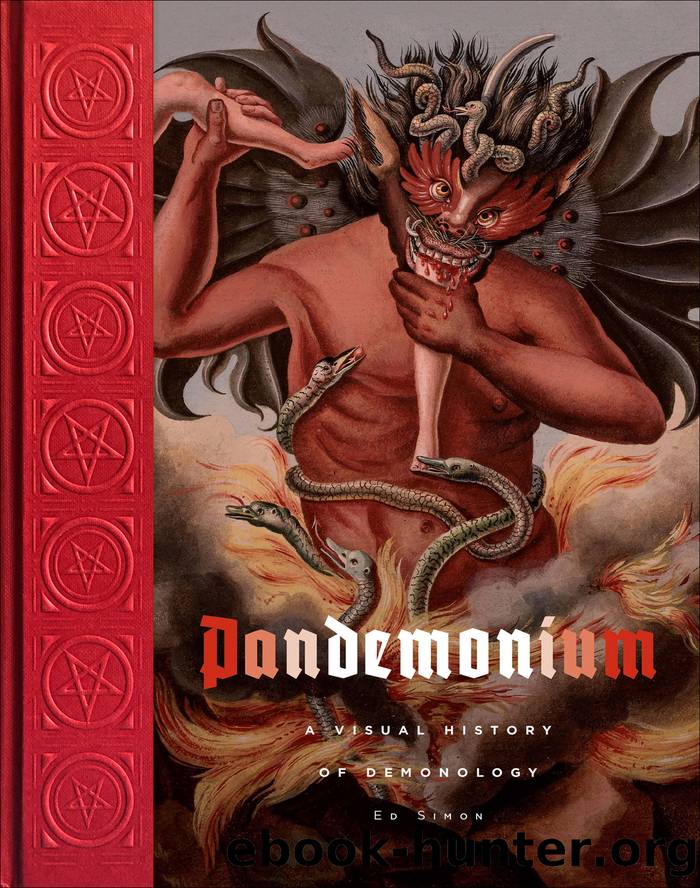

Pandemonium by Simon Ed;

Author:Simon, Ed;

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Cernunnos

Published: 2022-02-22T00:00:00+00:00

With arresting chiaroscuro, English painter Thomas Lawrence continued in the trend (quickly transforming into a tradition) of depicting Lucifer as a strong, muscular, and gorgeous classical hero in his 1797 painting (also entitled) Satan Summoning His Legions, housed at the gallery of the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

Mammon, Mulciber, and Moloch all serve logistical roles in the government and economy of hell, even while they disagree with their leader on the proper course of action to take. Mulciber, for example, operates as the chief architect of hell, and the demon who designed Pandemonium, with Milton drawing the character from Greek mythology; while Moloch, the bull-headed god of the ancient Philistines and Carthaginians, advocates for total war against heaven, burnishing his reputation as the demon to whom children were burnt in sacrifice. Mammon, by contrast, is more cowardly than rageful. True to his role as the demonic incarnation of avarice, he initially rejects the calls to a new war, seeing military incursion as a risk to the accumulation of wealth. âMammon, the least erected Spirit that fell/From Heavân,â as Milton describes him, âfor evân in Heavân his looks and thoughts/Were always downward bent, admiring more/The riches of Heavânâs pavement, trodden gold, /Than aught divine or holy else enjoyed/In vision beatific.â Miltonâs respect is clear, for though Lucifer waged war against the Lord, thereâs a dignity afforded to Satan thatâs denied to baser and cruder demons like greedy Mammon.

No character in Paradise Lost can match the full intensity of the greatest of demons, however. Not Beelzebub, or Belial, not Mulciber, Mammon, or Moloch. None of the archangels as rendered by Milton are as three-dimensionalâMichael, Gabriel, and Raphael all fall far short of him. Adam and Eve are flat when compared to the Serpent, and the abstractions of Sin, Death, and Chaos seem more allegory than personality when measured against Lucifer. Christ appears as a sanctimonious prig and God a boring authoritarian when placed in contrast to the greatest character of English literature, for against all of them, Miltonâs Lucifer is a triumph who rewrites the age itself. Never has such pathos been imbued unto a loser, never has such nobility been imparted to the rebel. âAlone the dreadful voyage; till at last/Satan, whom now transcendent glory raised/Above his fellows, with monarchal pride/Conscious of highest worth.â

Milton was, after all, a revolutionary, and one who advocated for the death of a king. Not only that, but the partisan of what would ultimately be a failed revolution, writing Paradise Lost in the seventh year of the reign of his adversaryâs son, imagining that âIncensed with indignation Satan stood/Unterrified, and like a comet burned.â Blakeâs contention regarding Milton is, despite the latterâs Christianity, hard not to find convincing.

Lucifer is at the center of any critique of Paradise Lost over the years, though the correct way to interpret him is ever variable. Arguably the demon of Miltonâs imagination is the progenitor of much of what would come to be called the âleft hand pathâ of theurgy in the Romantic era; that is occultism that embraced the potentiality of black magic.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Michelangelo And The Sistine Chapel by Andrew Graham-Dixon(1282)

The Geometry of Love by Margaret Visser(1145)

Accounts and Images of Six Kannon in Japan by Sherry D. Fowler(1143)

Seven Secrets of Shiva by Devdutt Pattanaik(1140)

The Mushroom in Christian Art by John A. Rush(1114)

Saints, Shrines and Pilgrims by Roger Rosewell(1101)

Resurrecting Easter by John Dominic Crossan(1091)

The Lost Painting by Jonathan Harr(1077)

Buddhism Illuminated by San San May Jana Igunma(1063)

THE FRESCO by The Fresco(1057)

Ayala's Angel by Anthony Trollope(1047)

Illuminated Manuscripts by Richard Hayman(1035)

The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols by Robert Beer(1030)

Creating Personal Mandalas by Cassia Cogger(997)

Silence and Beauty by Makoto Fujimura(977)

Moon by the Window by Shodo Harada(965)

Saint Paul by Pier Paolo Pasolini(949)

Dharma Delight by Rodney Alan Greenblat(936)

Art From The Sacred To The Profane: East by Schuon Frithjof(931)